CSC host to a legacy from noted Black artist

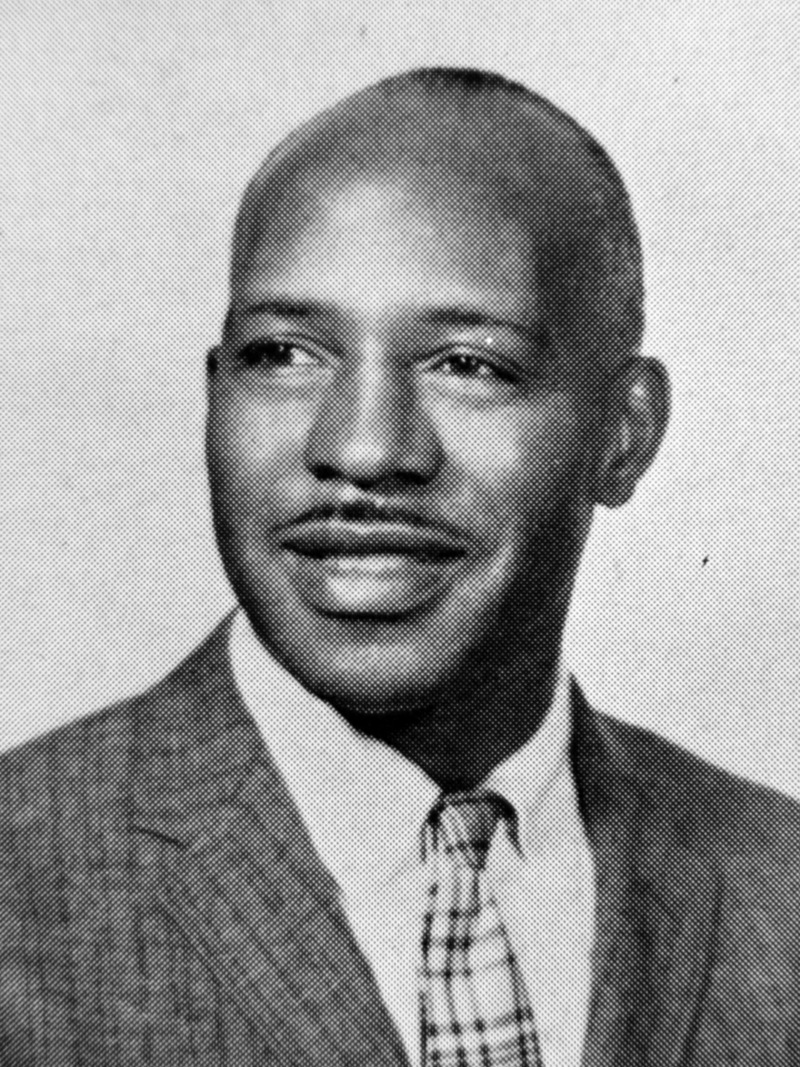

CHADRON – Nearly five decades after his departure from the Chadron State College arts faculty, African-American sculptor and ceramicist William (Bill) Artis and the legacy of his pieces in the college’s fine arts collection have received steadily growing attention.

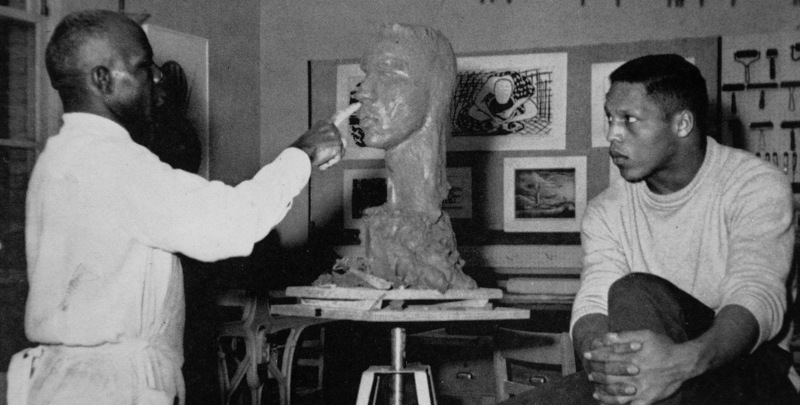

And even beyond the assortment of terra cotta and stoneware busts, ceramic vases and bowls, mosaics and drawings displayed at locations throughout the campus, awareness is also growing of the lasting impact the gifted artist and teacher had on the people he came in contact with during his tenure at CSC.

“He was a fine person, and a really excellent artist,” said Jean Boehle, whose husband, Bill, was the fine arts professor responsible for hiring Artis in 1954.

“He was very much a gentleman. I enjoyed having him as an instructor and a friend after graduating,” said Bob Yost, a 1964 graduate who donated several pieces of Artis’ work and a trove of correspondence and other papers to the college.

Artis, born in 1914 in North Carolina and a New York City resident from the age of 13, earned attention in the art world at a young age. He was just 18 when his plaster bust “Head of a Girl’ won a $100 John Hope prize in sculpture and earned him mention in Time magazine. The story said that Artis was a student who delivered newspapers and “lived chiefly on free lunches at his high school.”

It was the first of a number of articles in popular media about Artis, who had works in a several major exhibitions in the ‘30s and studied with Augusta Savage, a well-known artist and teacher in the Harlem Renaissance movement.

After serving in the U.S. Army during World War II, Artis earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in fine art from Syracuse University, where he trained under Ivan Mestrovic, a noted sculptor of the time.

An interest in the Sioux Indian culture appears to be the reason Artis made the great leap from the East Coast to the Pine Ridge reservation in South Dakota in the early ‘50s. There he taught at the Holy Rosary (now Red Cloud) School and supervised a pottery production project for two years. When he joined the CSC faculty as an assistant instructor in 1954, he brought two busts of Sioux people “sculptured using native clays which have won considerable attention,” the Chadron Record noted.

A life-long bachelor, Artis never learned to drive, and, as probably the only African-American in the small western community, he was sometimes picked up by police who wondered what a black man was doing walking the streets of Chadron.

Although one of his students, 1966 CSC graduate Eric Johnson, said the incidents embarrassed Artis, others say they don’t recall him mentioning any racial animosity.

“He was a black guy out here in the middle of nowhere but it did not affect him that I ever saw,” said Ken Korte, who took art classes with Artis in the early ’60s.

“He told me because he was black, ‘I have to be better than a white person,’” recalls Don Ruleaux, a CSC art student under Artis who went on to become an art teacher and achieve notoriety for his own paintings, drawings and silver point works.

As an instructor of sculpture and ceramics, Artis was popular with students, and effective at finding their strengths.

“He assumed we all had talents in the arts,” 1962 graduate Karol Griffith Talbot said in a 2011 letter to longtime CSC information director Con Marshall.

After directing students about what to do with their materials, Artis would watch “and give us pointers on how to improve our piece,” said Ruleaux. That was a welcome contrast to other teachers, who simply lectured and criticized students’ work, Ruleaux added.

“The students loved this man. They idealized him,” said CSC art professor Richard Bird, who helped rekindle interest in Artis in the 1990s.

The short, black man always wore a white shirt and tie to classes, donned an artist’s smock when working, and had a good sense of humor, his students recall. He would sometimes display a temper, however, “when a piece of pottery didn’t come off the wheel the way he wanted,” Yost said.

He was also generous, and many people report receiving pieces of his pottery or other items as gifts.

Though Artis was teaching at CSC and far removed from the art centers of the East Coast, his works continued to attract national attention, possibly because of summer sojourns back to the State University of New York at Alfred, where he had studied previously. He won top honors for sculpture at the National Art Exhibition in Atlanta several times in the ’50s and early ‘60s, had pieces selected for major museum collections, and became known particularly for his terra cotta figures and sculptures of African-American subjects.

His work in Chadron encompassed other media as well, and generated some controversy in 1959, when a large, brightly colored mural in a modernistic style, created as part of study for a doctoral degree, was installed in the foyer of Memorial Hall. Artis defended the piece as symbolic of man’s reaction to his environment, however, and the piece remained in place for some 25 years before it was removed during a 1984 remodeling.

Artis left his job at CSC in 1965, and struggled with depression for a time while living in California and New York and looking for another position.

“When fatigue and depression take over, the sensitive really suffer,” he wrote in a Feb. 11, 1966, letter to Yost. “I hope to get straightened out in a year or so and get back to gainful employment and creative production.”

Later that year Artis was hired as an instructor at Mankato (Minnesota) State College, where he taught until 1975. While there, his art work continued to gain recognition in national exhibitions, including a 1971 retrospective at Fisk University in Tennessee. In 1970 he was recognized at the annual meeting of the College Art Association in Washington, D.C. as an outstanding sculptor and ceramist, who played an important role in Afro-American art.

Artis died in Northport, New York, in 1977, after a lengthy illness, possibly from a brain tumor. He is buried in Long Island National Cemetery in New York.

Artis is now considered a pioneering figure in African-American sculpture and ceramics. His pieces are in important museum collections around the country, including the Smithsonian Institute and the Joslyn Museum in Omaha. Many of his works are in private hands as well and can command prices in the tens of thousands of dollars when they appear at arthouse auctions.

Chadron State may have the largest and most diverse collection of Artis’ pieces in the country, said Bird.

“We have the biggest array of work,” he said. “We’ve got pencil drawings, busts, some mosaics, ceramic sculptures and ceramic pots. He was known as a sculptor. Many places don’t know he did an oil painting now and then.”

The nucleus of CSC’s collection came from works Artis left behind at the time he left his teaching post. Bird said he discovered the pieces in storage when he arrived at CSC in 1988 and began using them in teaching.

“I’d put them in class for the students to look at,” he said.

As interest in Artis began to grow, Marshall, who had taken a class with him, remembered that students had served as models for some of the sculptures. He was able to identify the subjects of three of the busts and had labels made to name them.

Donations by alumni and others have added to the CSC collection, which now includes 25 pieces, and an archive of correspondence and photos.

One of the more recent acquisitions in the CSC collection was donated by alumna Annette (LaMay) Davies. The bust had belonged to her father, Joe LaMay, who was already an accomplished painter when he took classes with Artis in the ’60s and probably obtained it by trading for one of his own works, Davies said.

“My dad thought he (Artis) had lots of talent,” she said. “I thought ‘That (bust) needs to go back to Chadron.’”

Several Artis works are on display in Memorial Hall, with others at the Sandoz Center and the Alumni Foundation office. One of the Artis busts, which was accidentally damaged in 2012, was repaired at the Gerald R. Ford Conservation Center in Omaha, and returned to the college in October 2014.

The pioneering African-American sculptor left another, less tangible legacy as well, in the inspiration and guidance he gave to students.

“My career in teaching was very art-based due to Dr. Artis’ influence,” said Talbot.

Ruleaux, who remained friends with Artis for years after both had moved away from Chadron, received valuable guidance from his former instructor.

“He told me ‘You have to have food, clothing and lodging. Become a teacher and do your art on the side.’”

That advice led Ruleaux to a 45-year-long teaching career that included a decade at CSC, as well as multiple awards for the art he created “on the side.”

Artis’ influence extended to students who didn’t pursue careers in art. Yost, a business major who at one time set up a gallery in Scottsbluff to try selling some of Artis’ work, remembers him more as a friend than a teacher.

“I always felt flattered that he would take on a student as he did me,” he said. “I wasn’t a good artist.”

Korte also learned much from Artis.

“He taught me a lot,” said Korte, who became a curator and then director of the Montana State Historical Society, and later was interim director at the Mari Sandoz High Plains Heritage Center. “I always used my art background.”

A 2011 post on a website that has information about Artis’ burial place (findagrave.com) tells a similar story. “Thanks for the ceramics classes I had in 1962 at CSC. I still have my large vase you helped me form.” wrote Richard Stratton, a 1962 physics and mathematics graduate.

Current and future students also benefit from Artis’ legacy, thanks to monetary donations made in his name. Mike Chipperfield, a retired Ohio University art professor who studied under Artis and graduated from CSC in 1964, spearheaded an effort to start a scholarship endowment in Artis' name. The Chadron State Foundation began awarding scholarships from that account in 2005-2006. It is open to students at sophomore level or higher majoring in visual arts, and the award is based on artistic and creative ability, as judged by the CSC art faculty.

“We hear stories about William Artis from alumni and friends across the nation,” said Foundation Executive Director, Connie Rasmussen. “We are proud of the unique Artis collection we have now and are grateful to the many alumni who have donated pieces of his work to the collection. It is our hope to have a permanent, revolving display of Bill Artis pieces and would like CSC to be a permanent home for more of the work of this gifted artist and teacher.”

Category: Art, Campus News