Mine safety manager touts uranium's positives

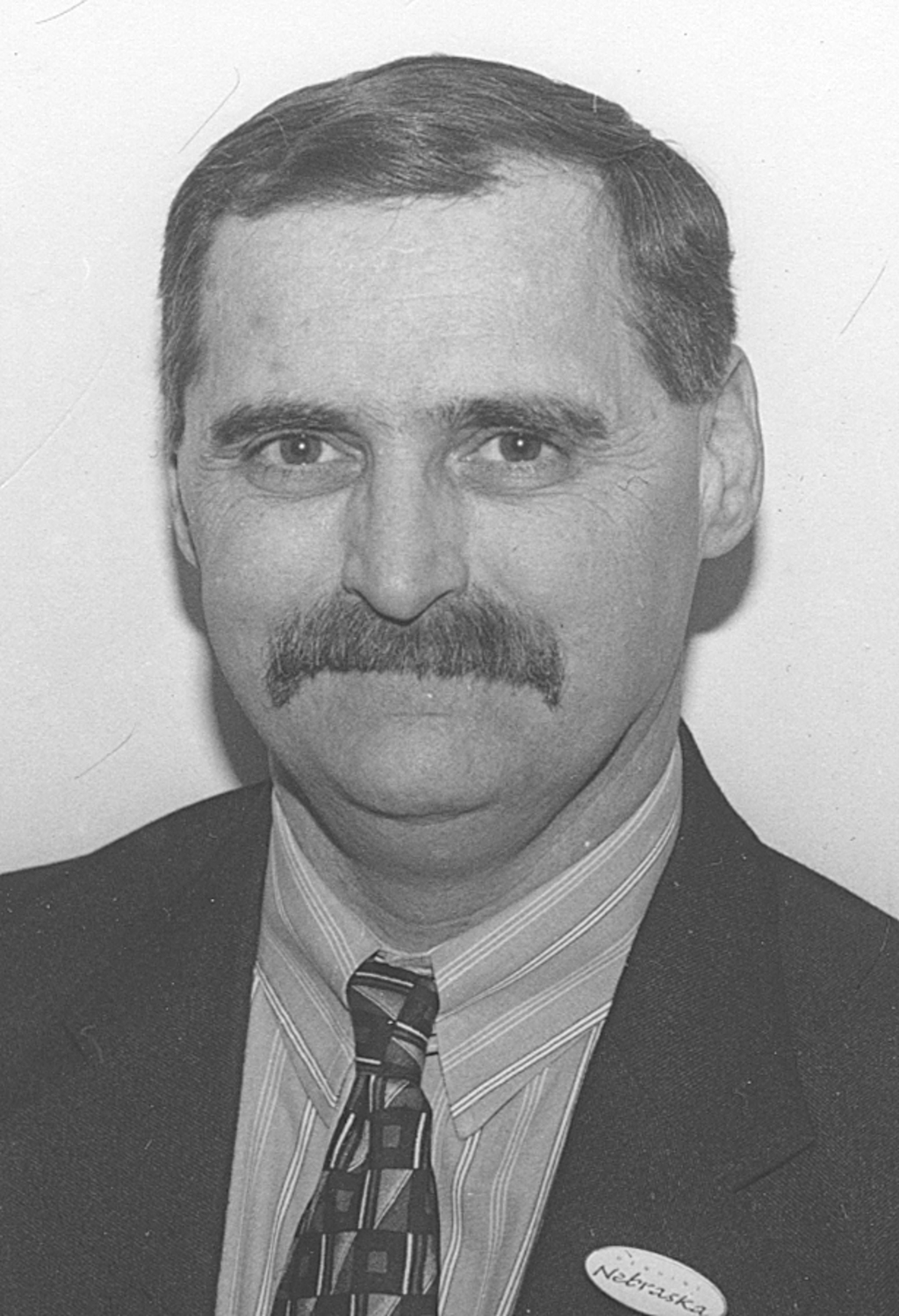

Larry Teahon, manager of health safety and environmental affairs for Cameco Resources' Crow Butte Operation near Crawford, touted the benefits of uranium mining during the fall's final installment of the Graves Lecture Series at Chadron State College earlier this month.

Teahon, who is one of 12 employees at the mine who focus on safety, said personal safety and environmental safety are two of Cameco's foremost values. He also said the company works to support communities and make money for its shareholders.

The speaker said the mine receives much scrutiny and is highly regulated by environmental agencies. He listed more than a half dozen permits that the operation is required to carry.

Teahon said the mine makes a large local economic impact by employing 66 people and 20 contractors. It also buys locally whenever possible and pays about $38,000 in taxes per employee each year. Nebraska businesses received $6.3 million of revenue from the mine last year, he said.

He said all uranium from Crow Butte is used for power generation and most is sold in the United States. He said nuclear energy is more efficient than gas and oil, and accounts for 16 percent of electricity produced.

"I wouldn't work there if they were using our uranium to build weapons," he said.

The Crow Butte facility has been producing uranium since 1991. Teahon said there is only one other uranium mining operation in the United States. Crow Butte became wholly owned by Canada-based Cameco in 2000.

Teahon gave a summary of how the process works.

A solution containing baking soda and oxygen is inserted to six injection wells that encircle each recovery well. The process loosens uranium from sandstone in the underlying formation and returns the product to the surface. After several processing steps, the uranium is placed in 55 gallon drums as a powder. The Crow Butte Operation produced 2.8 million pounds of uranium in 2007. The most uranium collected by any of the company's mines was 15 million pounds.

Teahon said the annual water usage for the mine is equivalent to that of one center pivot of corn.

The operation has 377 monitor wells, both deep and shallow, that are observed to make sure no mining solution is moving outside the well pattern. Each is checked every two weeks by two employees who have full-time jobs taking water samples from those wells.

Teahon said employees wear badges to detect radiation, and the annual working limit exposure for people at the mine is the equivalent of about one x-ray per year.

"If you do a lot of flying, you're exposed to more radiation than we are," he said.

Although Teahon precluded his presentation by saying he would not address the proposed expansion or license renewal of the mine, a few audience members asked tough questions about the mining process.

One audience member asked about a leak at the plant that occurred in recent years.

"During a mechanical integrity test, we found a crack in the pipe," Teahon said. "So, it's a mathematical calculation. We know we've recovered this amount, the rest either went into the formation - which is probably where it went, but we can't tell you that with 100 percent certainty. We know that it's not in the area we cleaned up."

Another asked about the challenge of nuclear waste disposal. Teahon agreed that it's a worldwide problem, but said there is not as much of it as people might think.

"If you would take all of nuclear waste in the world today, and there are more than 440 reactors, that waste would cover one football field 15 foot thick," he said. "As far as a footprint goes, you're not talking a lot."

Teahon said many people confuse uranium with radium, which has a history of causing health problems.

"Uranium won't penetrate more than a little over an inch in the air and it won't penetrate the dead layers of skin," he said. "It's like any other heavy metal. It does damage to you if you get it in your body."

He said people at the mine who are potentially exposed to airborne uranium wear respirators.

If uranium were to be become exposed by an occurrence such as a vehicle accident, Teahon said the powder could be watered down, covered and picked up with no long-term effects to the environment.

Teahon, who is completing his seventh year as a member of the Nebraska State College System Board of Trustees, was Chadron's city manager for eight years ending in 2005.

Category: Campus News, Health Services